When a startup begins shaping its product vision, one of the biggest challenges is deciding how to validate ideas before committing to full-scale development. Terms like MVP, PoC, and prototype are frequently used in product discussions, but they’re often misunderstood or even used interchangeably. For founders, consultants, and startup teams, this confusion can lead to wasted resources, wrong priorities, and missed opportunities.

So, what’s the real difference between MVP vs PoC vs prototype? When should you choose one over the other? And how do these approaches fit into early product planning?

In this article, we’ll take a deep dive into the three concepts, explore their roles in product development, compare them side by side, and help you decide which approach fits your startup journey.

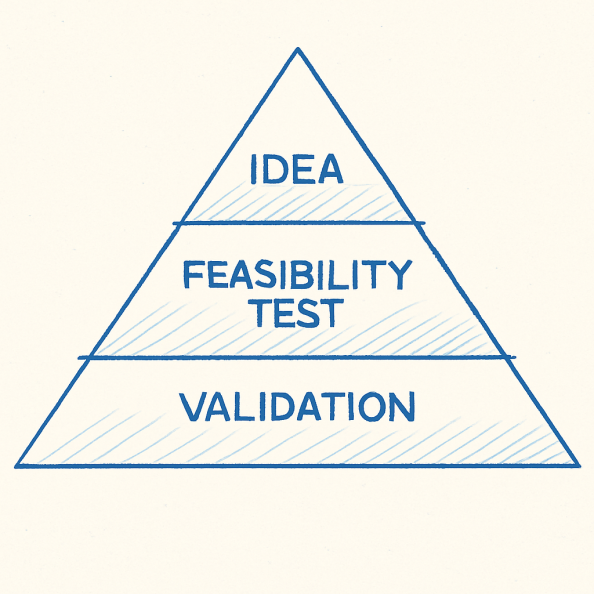

A Proof of Concept (PoC) is an experiment designed to verify whether a certain idea, technology, or assumption is feasible. The goal of a PoC isn’t to build a market-ready product but to answer one simple question: “Can this be done?”

Purpose: Validate the technical feasibility of an idea.

Output: A working demonstration or experiment, not a full product.

Effort: Small team, minimal design, short timeframe.

Risk reduction: Helps avoid costly mistakes before investing in development.

Imagine a startup wants to build an AI-powered language app that can translate speech in real time. Before designing the app or launching an MVP, the team would run a PoC to check if existing AI models and APIs can handle speech recognition and instant translation without major latency.

If the PoC shows technical feasibility, the startup can move to the next stage. If not, they pivot before wasting money.

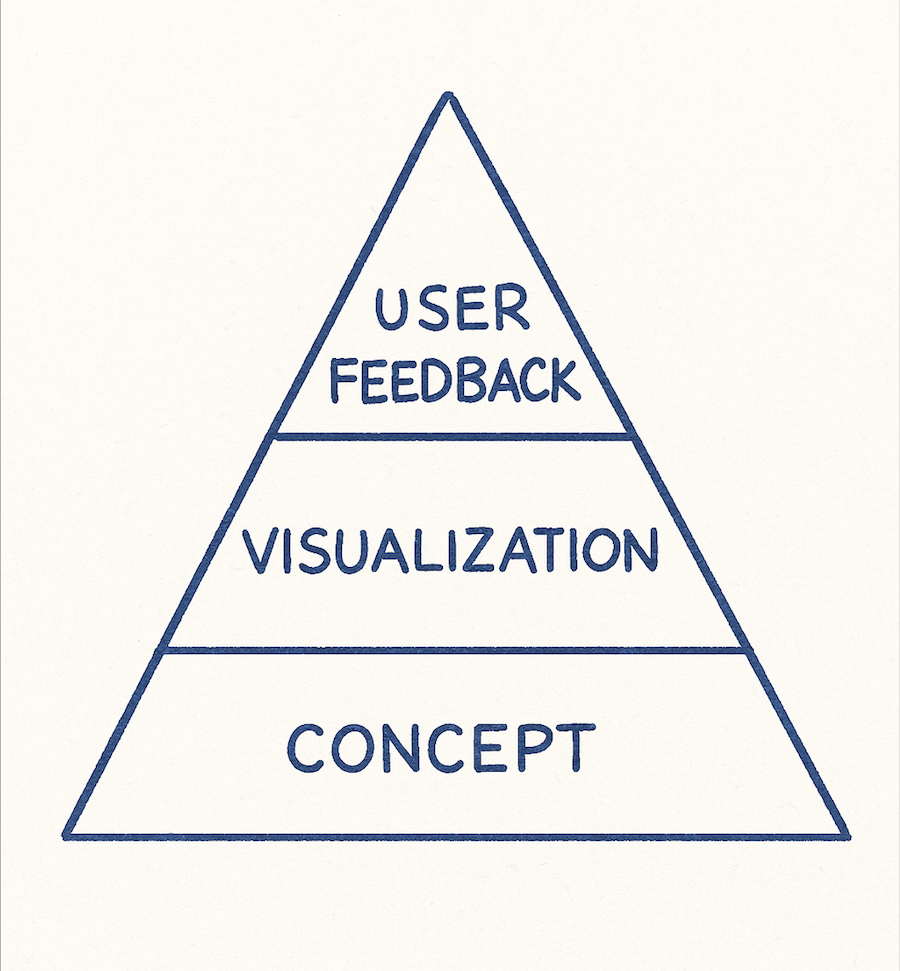

A prototype is an early visual or interactive representation of a product idea. Unlike a PoC, a prototype doesn’t prove technical feasibility—it’s about showing how the product will look and feel.

Purpose: Explore user experience (UX) and design.

Output: Low-fidelity sketches or high-fidelity interactive mockups.

Audience: Founders, investors, product teams, and test users.

Effort: Design-focused, created with tools like Figma, Sketch, or InVision.

Suppose you’re developing a mobile payment app. Instead of writing code, you first create a clickable Figma prototype to visualize screens, flows, and interactions. You can then use this prototype in user interviews or investor pitches to gather feedback early on.

Prototypes save time by clarifying design assumptions and preventing expensive redesigns later.

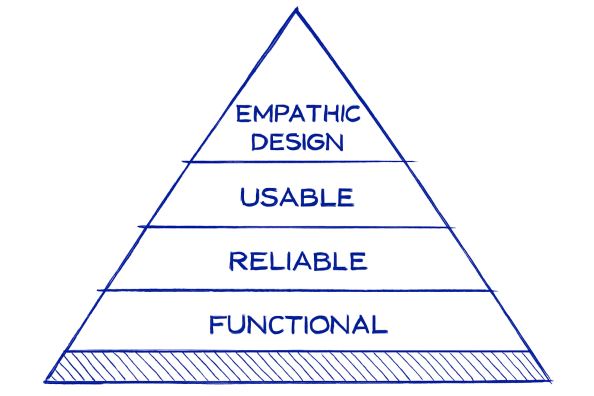

The Minimum Viable Product (MVP) is a simplified but functional version of a product, released to real users for testing in the market. Unlike a PoC or prototype, an MVP is a working product with core features. Its main purpose is MVP validation—checking whether the market wants and needs the solution.

Launching an MVP allows teams to:

Dropbox is one of the most cited MVP success stories. Instead of immediately building a complex file-syncing system, the founders created a simple demo video explaining the concept. The huge interest validated the market demand. Later, they launched an MVP version of Dropbox to early users and refined it based on real feedback.

This process illustrates how an MVP allows startups to validate assumptions in practice, not theory.

Now that we’ve defined each concept, let’s explore the differences between PoC vs prototype vs MVP.

| Aspect | Proof of Concept (PoC) | Prototype | Minimum Viable Product (MVP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goal | Prove technical feasibility | Demonstrate design & UX | Validate product-market fit |

| Focus | “Can we build it?” | “How will it look & feel?” | “Do users want it?” |

| Audience | Internal team, tech leads, investors | Users, investors, design team | Real customers & early adopters |

| Output | Working experiment or test | Clickable demo, visual mockups | Functional but minimal product |

| Cost | Low | Moderate | Higher (requires development) |

| Risk addressed | Technical | Usability & design | Market demand |

| When to use | Very early stage, idea validation | Before MVP, for design testing | After validation of feasibility & design |

This table highlights why confusing these concepts can lead to mistakes. A startup that skips PoC may later face technical barriers. One that skips prototyping may invest in building features with poor usability. And one that skips an MVP may launch a full product only to discover no real demand.

The decision between MVP vs PoC vs prototype depends on your current stage, resources, and goals.

The key is aligning your approach with your early product planning strategy. Startups that follow this progression: PoC → Prototype → MVP tend to reduce risks at each stage while ensuring faster time-to-market.

In recent years, artificial intelligence has become a powerful tool in shaping MVPs. AI can help startups speed up validation by automating testing, analyzing user feedback, and even generating design alternatives.

For instance, many founders now explore how AI assists in customer segmentation or feature prioritization during the MVP stage. If you want to learn more about this intersection, check out our article on AI and MVP — it explains how artificial intelligence is reshaping early product strategies.

When Dropbox was first conceived, the idea of seamless cloud file synchronization seemed revolutionary. But instead of spending months building complex infrastructure, founder Drew Houston created a simple MVP: a short demo video showing how the product would work.

Uber’s journey began with a prototype called “UberCab.” The first version of the app was very basic—it only allowed users to request a black car in San Francisco.

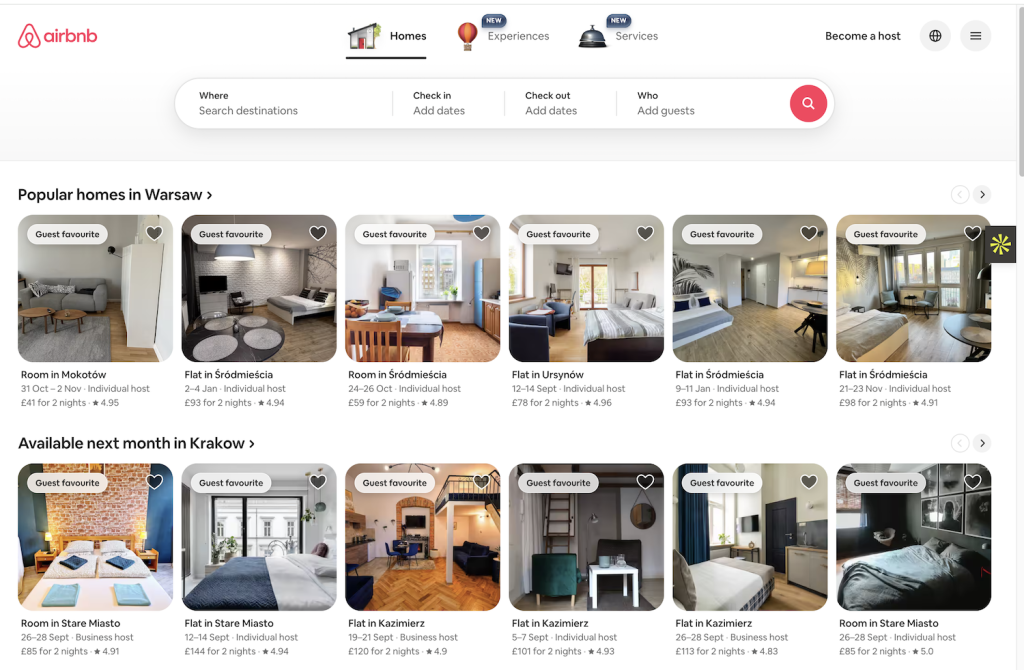

In 2007, Airbnb founders couldn’t afford rent in San Francisco. They set up a basic website to rent out air mattresses in their apartment to conference attendees.

Spotify needed to prove two things before becoming a global music leader:

Result: The MVP attracted enough traction and investor interest to secure funding and scale.

Lesson: Combining PoC validation with an MVP rollout can be a powerful formula for success.

Before Zappos became a billion-dollar online shoe retailer, founder Nick Swinmurn tested the concept with a minimal MVP. He didn’t buy inventory upfront. Instead, he took photos of shoes in local stores, posted them online, and only purchased the shoes when someone ordered.

Result: This experiment validated both customer demand and willingness to buy shoes online.

Lesson: MVPs can be scrappy—sometimes they’re more about testing business models than building full platforms.

From PoC experiments that test raw feasibility to prototypes that shape the user journey and MVPs that validate demand, each step plays a unique role in the startup lifecycle. Real-world success stories show that companies like Airbnb, Uber, and Dropbox didn’t skip validation—they followed structured paths aligned with their early product planning.

For founders and consultants, the choice between MVP vs PoC vs prototype isn’t academic—it’s a roadmap to building products people actually want.

Ready to Build Your MVP?

Turn your idea into a real product with our MVP development services.

We’ll help you validate your concept, prioritize features, and launch faster.